We'll meet again, don't know where, don't know when...

The Beginning

When all you have is a gun, everything is a foot. No statement has ever been as true when letting an undergrad work with C programming. At Purdue, all computer science undergrads take CS240 - Programming with C. While segfaults, memory leaks, and double frees are common when learning C for the first time, the bite sized homeworks in CS240 allowed for a very soft introduction. Large-scale logic and implementation issues never manifested themselves in our code. There simply was not enough lines to fall into a deep pit of hair pulling. After passing CS240, however, you get a semester to mentally prepare yourself for the goliath…

Systems Programming

At this point, the average CS student had completely forgotten what a pointer was. Learning about data structures and algorithms along with hardware architecture had taken over the space in our brain concerned with memory management. Yet an immediate reallocation is needed in that part of our hippocampus, as the first project is implementing malloc() and free().

Fenceposts and Frustrations

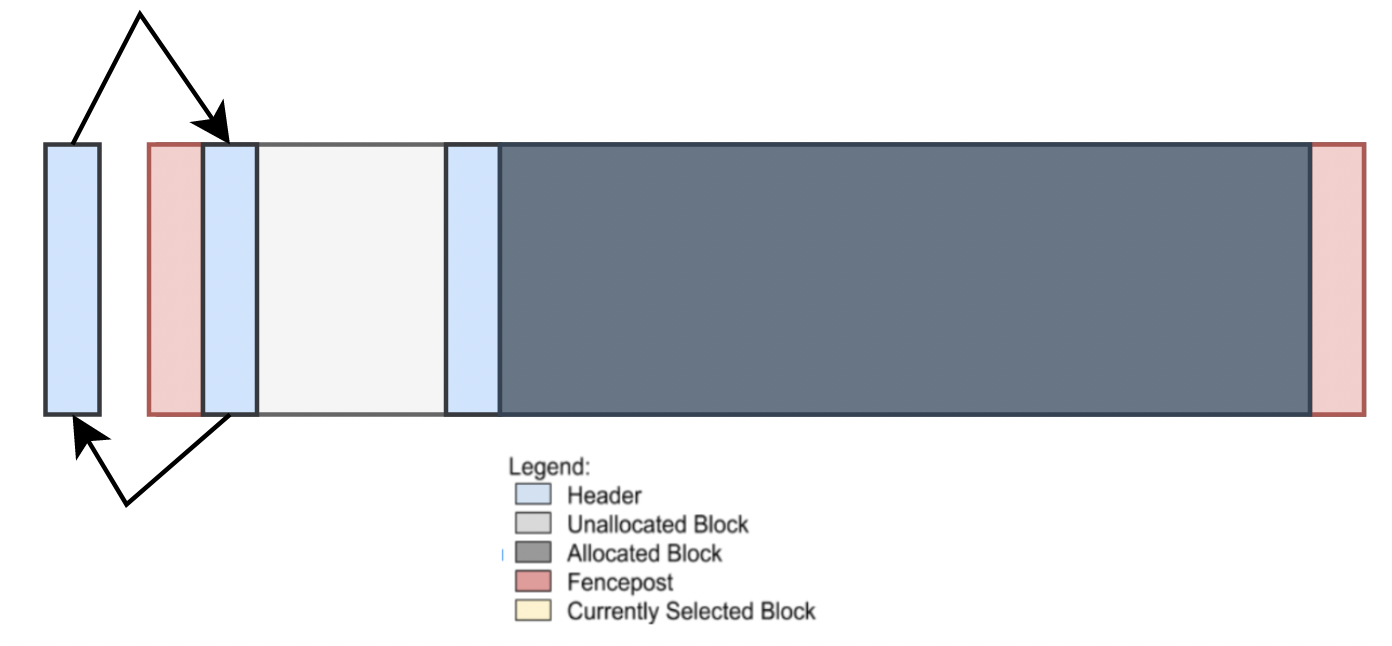

The first step when approaching any systems programming project is crucial. Read. The damn. Documentation. But like every good undergrad, I decided the docs were a waste of bytes and dove straight in. For those who need a refresher on the basic understanding of how dynamic memory works, lets use some diagrams to visualize the problem.

Dynamic memory (that is, memory allocated at runtime) is stored in a section of computer memory called the heap. When you run out of space, you can use the Unix command sbrk() to shrink or extend the heap. However, this implementation results in less than ideal consequences. When you want to deallocate memory, you can only deallocate the block if it falls right at the end of the heap. If the block is somewhere in the middle, you would have to possibly deallocate the right-most blocks first. As a result, we have the malloc() and free() functions that take care of this process.

Here is a more detailed look at what our heap will look like. Each block of allocatable memory will have a header. This header contains the total size, the size of the left block, and pointers if it is unallocated. These pointers point to the next block of allocatable memory (we call this the free list). The free list is organized by the size of the block, but the exact layout of this list is trivial for this write-up. If we free an allocated block, we must also check if the blocks on our left and right are unallocated. If they are, we can combine them all into one larger block of unallocated memory (this is called coalescing). Along with our allocated and unallocated blocks we have our fenceposts. Fenceposts are headers that have been set to the FENCEPOST state using an enum. They allow us to determine where our heap ends so we don’t try to process inaccessible memory. The enum layout is:

enum my_state {

UNALLOCATED = 0,

ALLOCATED = 1,

FENCEPOST = 2

};

You might ask, “where is this information stored?” The enum containing the state of the block was never mentioned as being part of the header, so where is it? Here’s the fun part. All the sizes our blocks of memory will be a multiple of 8 (as is standard), meaning that the binary representation of the size variable stored in the header will always have 000 at the end. We can use these unused bits to store our state:

head->header_size_state = (head->header_size_state & ~0x3) | state;

Here we first wipe the existing state with (head->size_and_state & ~0x3). Then we bitwise or it with the given state, thus giving us free room for storage.

Addressing Coalescing

Now that we have a basic understanding of what the heap looks like, what happens when we run out space? Assuming we have no free block large enough to satisfy a request, we must call sbrk() to request more heap space from the OS. The exact size we request is a constant called ARENA_SIZE which in this instance is 4096 bytes (for more information about what this is and why, check out page tables). We have functions that will set up the fenceposts and the unallocated header in this new chunk of memory. If this new chunk is not adjacent to our past chunk in memory, we can simply add the new unallocated block to our free list. However, if they are adjacent, then we must coalesce the two chunks together. This means we must get rid of the fenceposts that are touching each other in the middle of our chunk and make them apart of our unallocated block. If there is a unallocated block at the end of our first chunk that must also be added to our large unallocated block. Such coalescing can be visualized here:

The Customer Is (Not) Always Right

Now that the basic understanding of implementation is established, we now get to start programming! One of the first things that needs to be addressed in allocate_object() (our function for allocating memory for the user) is how to handle the user’s size request. The size the user enters might have some issues. First, the size_state variable in our header struct includes the size of the header. Therefore in our request size we must also add on the size of our header. Second, the raw size might not be a multiple 8, meaning we have to round it up for them. Lastly, if the whole size is still less than the size of our header after these adjustments, we should go ahead and request at least this size. First, lets add on our header size:

size_t whole_size = raw_size + ALLOC_HEADER_SIZE;

You might be curious as to why we use the constant ALLOC_HEADER_SIZE and not sizeof(header). This is because an allocated header is smaller than an unallocated header due to the absence of our two free list pointers. Thus our preprocessor line is:

#define ALLOC_HEADER_SIZE (sizeof(header) - (2 * sizeof(header *)))

Next, lets round this up to a multiple of 8:

if (whole_size % 8 != 0) {

whole_size += (8-(whole_size % 8));

}

Lastly we need to check if our whole size is less than the size of a header.

if (whole_size < sizeof(header)) {

whole_size = sizeof(header);

}

Putting this all together we get:

header * allocate_object(size_t raw_size) {

if (raw_size <= 0) { // If our user is an idiot...

return NULL;

}

size_t whole_size = raw_size + ALLOC_HEADER_SIZE;

if (whole_size % 8 != 0) {

whole_size += (8-(whole_size % 8));

}

if (whole_size < sizeof(header)) {

whole_size = sizeof(header);

}

...

}

The Oak and the Fern - Lessons Learned

My experience working on this project was - and i mean this earnestly - crucial in forming my opinions on C. While I definitely enjoyed my time in CS240, I think working on a large scale and difficult project made me appreciate C a lot more. In the past, I have resisted using C and going deeper under the hood of computers. Remember, I am a math major after all, and the computational aspects of computer science are my niche. However, much like the fern in Aesop’s famous tale, I found that allowing myself to embrace C and systems programming made me appreciate this lower-level programming a lot more. For all the SEGFAULTS, double frees, and undefined behaviors I programmed, it got me one step closer to loving working with low-level systems. C is a dangerous language, but once you shake off your initial fears (and buy the famous K&R book), you too can learn to stop worrying and love the SIGSEGV.